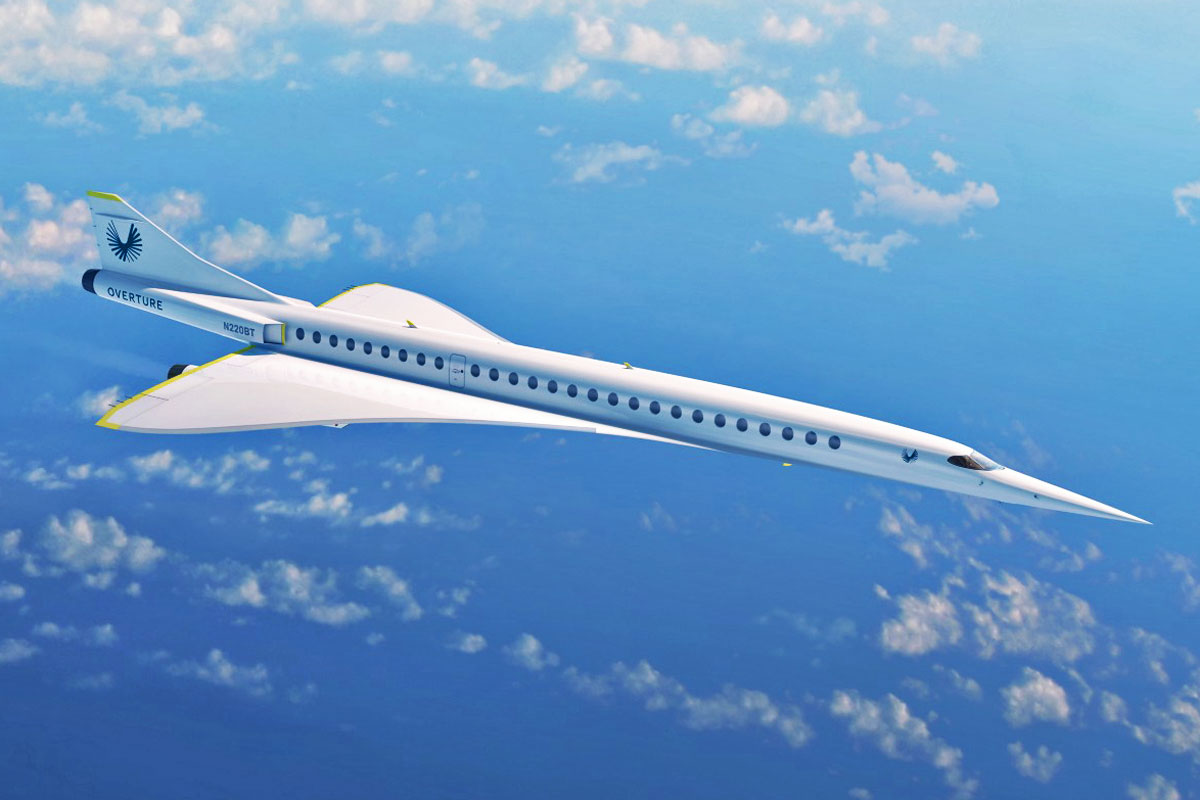

In a small, discreet hangar at Centennial Airport, on the outskirts of Denver, Colorado, a possible revolution in air travel is happening right now. That’s where Boom Supersonic is located, a startup founded in 2014 by Blake Scholl, a former software engineer at Amazon who decided to create a supersonic passenger plane after seeing the Concorde at a museum.

Scholl achieved what seemed impossible for someone who had not been in the aeronautical field until then, to obtain investment from several venture capital funds for his project, a jet capable of flying at Mach 2.2 carrying between 55 and 75 passengers in addition to six crew members over distances of up to 4,500 nautical miles (8,300 km).

The Overture program is making great strides and is expected to introduce the XB-1 in 2020, a concept that is one-third the scale of the series aircraft. With it, Boom intends to prove that the project is capable of meeting the requirements of a civilian supersonic: flying a considerable distance and at a speed almost three times that of a Boeing or Airbus, but consuming little fuel and, above all, in a “silent” way. By silent, we mean an aircraft that emits acceptable noise in an urban environment, the biggest challenge of the new supersonic airplanes.

Here is a great mystery of Boom. While other initiatives are still struggling and NASA and Lockheed Martin are at an early stage to validate technologies capable of producing a viable supersonic plane, Scholl’s company already has interested customers, Japan Air Lines and Virgin Atlantic.

But why can Overture become the first independently built civilian supersonic plane? The answers have been given by the CEO himself in recent years.

Concorde dinosaur

In a 2017 article, the executive compared Overture to Concorde to clarify how his project will be able to do what the Anglo-French jet failed. “Concorde was designed 50 years ago with slide rules and wind tunnels; today we have the benefit of half a century of improvements in aerodynamics, materials, and propulsion. These technologies combine to enable an aircraft that is both faster and more efficient than Concorde“, explained Scholl.

Among the differentials of the new aircraft are the carbon fiber fuselage with an “area ruled” design and much more efficient engines. The carbon composites he explains, allows “create a strong and lightweight structure in any dynamic shape desired”. Concorde, with an aluminum airframe, was impractical.

The material used in Overture also allows it to handle higher temperatures, which reach between 152ºC to 177ºC, at a speed of Mach 2.2. Concorde was only Mach 2 for that reason.

The European supersonic used a military resource, the afterburner, which added 17% more thrust to the engines, however, increased fuel consumption by 87%. Currently, turbofans are more powerful and economical, but in the case of a supersonic it is not possible to use engines with a high-bypass-ratio as we see in jets like the A320neo or the 737 Max.

The solution adopted by Boom will be to use medium-bypass turbofans without afterburner, but with a variable geometry intake and exhaust system. Both the Overture and the XB-1 will be equipped with three of these engines, which is also surprising.

To avoid the supersonic boom (not its name), the jet will depend on the design of its fuselage and wings so that the breaking of the sound barrier produces small, separate explosions that do not disturb people on the ground. It was this problem that caused Concorde to be banned from flying above Mach 1 within the USA.

Half a billion potential trips

To justify the high investment, the new supersonic aircraft have something in common, a wealthy public. It is not very different from the times of Concorde, which flew regularly only between New York and London or Paris with passengers who mixed celebrities and C-level executives, the only ones who managed to afford their expensive tickets.

While other projects aim at supersonic business jets, Boom preferred to design a commercial plane equipped only with business class. The reason is that 12% of commercial aviation passengers (almost 500 million trips by year) pays for this comfort and the goal is that the cost of Overture tickets be similar – much less, therefore, than Concorde.

There will be individual seats without wide width, after all, the duration of the flight will be much shorter. The windows will be huge, unlike the Concorde, and each seat will have a large touchscreen.

Boom does not talk about price, but Overture has a list of interested parties that have pre-booked about 75 planes. JAL and Virgin, as we said, are among them, but given the recent problems, they may not appear in this backlog in the future.

None of this seems to diminish Blake Scholl’s optimism. This week, the XB-1 received its wings and begins to take shape in the hangar in Denver. If all goes as expected, the expressive aircraft will be unveiled in the coming months and then taken to Mojave where it will conduct its test flights. The location could not be more appropriate. The California desert airport is home to companies like Stratolaunch, Scaled Composites and Virgin Galactic.

If Boom proves that it is capable of delivering what was promised, it must have exciting years ahead of it when leading the return to supersonic passenger flights. “We have seen measurable progress in almost every area of human achievement, yet somehow flights today take the same amount of time they took in the 1950s. We can do better“, believes the company.