The 1960s was of immense transformation in the commercial aviation. If at the beginning of this decade, jets were still a novelty in air transport, dominated by propeller engines, ten years later we were already experiencing the excitement of seeing giant or supersonic aircraft foretelling a unique era in air travel.

The year 1969 saw a catharsis in the aeronautics industry with the first flights of the Boeing 747, the largest commercial aircraft ever seen, and the supersonic Concorde and Tu-144 (this at the end of the previous year). But it was an apparently less superlative project that predicted what commercial aviation would look like 50 years later, the A300.

The world’s first twin-engine widebody had its official launch on 29 May 1969 when the French and German governments signed what would be the basis for creating Airbus, currently the world’s largest commercial aircraft manufacturer.

Half a century ago, however, betting on a big two-engine airplane sounded like a joke. The turbofan engines of the time still lacked such reliability to allow these planes to fly far away from alternative airports. It was common practice for mid-range jets to have at least three engines like the Boeing 727, the Trident or the Tu-154.

It is true that aviation already saw the first two-engine jets in action, but on short routes in denser areas where there were plenty of airports. During the decade famous planes like the DC-9 and the 737 appeared but without predicting its future success.

So what about a giant two-engined airplane? It seemed absurd, but it was in betting on this formula that Airbus opened a hard way to consolidate.

Before Airbus

Despite the lack of reliability of the engines, the proposal of a large capacity twin engine showed great advantages. By removing one or two engines it was possible to reduce weight and increase fuel efficiency, although this was not a problem at that time. Still.

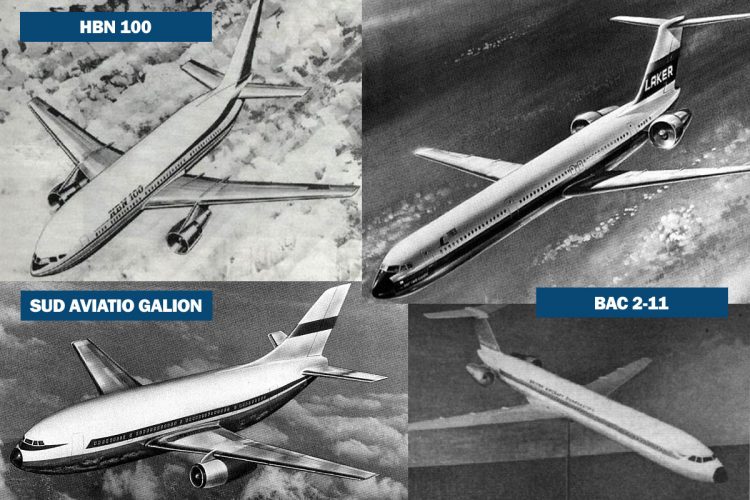

But whoever imagined a twin-engine wide-aisle jet was not Airbus but some European manufacturers like British Aircraft Corporation (BAC) with 2-11, Sud Aviation with Galion and the HBN 100 project, developed at the time by Hawker Siddeley, Nord Aviation and Breguet.

In common, they brought similar solutions such as capacity for more than 200 passengers, wider fuselage and only two engines. It was the HBN 100, however, that more fit into what would in the future be the A300, the first Airbus aircraft.

European Union

The post-war saw important initiatives by European manufacturers such as de Havilland Comet, the world’s first commercial jet, or Sud Aviation Caravelle, the elegant French twin engine, but it is a fact that Americans simply dominated commercial aviation, first with Douglas and Lockheed and then with Boeing.

With a unique domestic market and several manufacturers, the US has taken the lead in the industry and massacred projects such as BAC One-Eleven, HS Trident, Vickers VC-10, Caravelle and Dassault’s rare Mercure.

In the view of the French, German and British governments, any isolated initiative would not be a match for the Americans, so the solution was to join forces.

It was this thought in mind that these countries took the first steps to create Airbus in 1967. French and English were already together in the Concorde project, but it was already known that the supersonic jet had a more limited market. A large-scale production aircraft was needed to maintain jobs in Europe.

Trijets against twin-engine

Airbus’s A300 program (“A” from Airbus and “300” from passenger capacity) initially consolidated as a direct rival of the McDonnell Douglas DC-10 and Lockheed L-1011 Tristar, but with only two engines versus three of them.

Rolls-Royce committed itself to developing a more powerful version of the RB211 turbofan named RB207, but the English company, which was under-resourced at the time, decided to focus only on the first and would be exclusive of the Lockheed jet – an immense commercial failure, by the way.

Without having a suitable engine and with doubts about the demand for an immense jet like the original A300 and that would be greater until a Boeing 777, the “parents” of the aircraft decided to reduce its size to take 250 passengers in distances of 1,200 nautical miles ( 2.220 km).

New members

It was this plane that emerged at the Paris Air Show 50 years ago, the A300B, a huge surprise for the time. Cooperation between the three countries had been broken by the withdrawal of the British, but only partially. If the UK government decided not to invest in the project, Hawker Siddeley went ahead, being responsible for the wings, which had a unique aerodynamic refinement in the segment.

With the downsizing, the A300B was able to use any of the most advanced turbofans of the era, JT9D (Pratt & Whitney), CF6-50 (GE) and RB211 (RR), unlike American widebodies that were designed with original engines.

By opting for existing turbofans, Airbus has saved resources that were used to make the A300 a cutting-edge aircraft. In addition to being lighter due to the smaller number of engines, the wide body debuted composite materials in some parts as the leading edge of the wings and tail, something unthinkable at the time but which became common in new jets like the A350 and 787.

The fuselage diameter, which was 6.4 meters in the original A300, was reduced to 5.6 meters, however, Airbus designers decided to raise the floor of the passenger cabin so that it could receive two LD3 pallets side by side.

Although it is possible to use any turbofan, Airbus chose the CF6-50A, 49,000 lbs. of thrust. The reason is that GE would have the support of France’s Snecma, in a partnership that would later grow in the form of the CFM association.

Curiously, however, the first A300B proved to be small for Airbus’s first customer, Air France, which requested a slightly longer variant, the B2, with 270 seats and which became standard until the launch of B4, with more autonomy.

When the first prototype of the A300 flew in September 1972, Airbus had already changed its society several times. If France and England were to have led the consortium, followed by Germany, the withdrawal of the British made the French and Germans the main partners, with 50% each and represented by Aerospatiale (born of the junction of Sud Aviation and Nord Aviation) and Deustche Airbus, a joint venture between Messerschmitt-Bölkow-Blohm (MBB) with 65% and VFW-Fokker with 35% – Hawker Siddeley, in turn, was only a subcontractor in the beginning.

In 1971, the Spanish CASA joined the group with a 4.2% stake. When major manufacturers joined under the umbrella of state-owned British Aerospace in 1977, the United Kingdom once again integrated Airbus with 20% of the shares.

Bad start of sales

If in theory, Airbus and its aircraft looked like the ideal formula even after the oil crises completely changed the scene of commercial aviation, convincing airlines to buy the A300 was a difficult task.

From the beginning, the consortium leaders had in mind that without gaining customers in the US, the company would have no future. To reach this goal, the Europeans set off on a world tour in 1973 and passed through Brazil and Mexico before heading to the US where it was presented to major airlines but without a single plane sold.

Until then, Airbus had only been able to sell six A300s to Air France and three to Lufthansa, naturally candidates to use it under the influence of their countries. The airplane problem, however, was the small range, which motivated Airbus to create the B4 version with an extra tank of fuel. With high autonomy, the A300 was ordered by Korean Air in 1974, shortly after entering service.

But even able to consume 20% less fuel than a DC-10, sales of the A300 did not take off. Airbus then decided to be more aggressive in dealing with several airlines, especially in Asia, where the jet seemed to be better understood. Inquiries from Indian Airlines and Thai Airways came in addition to requests from Air Inter and South African Airways, but no customer in the US.

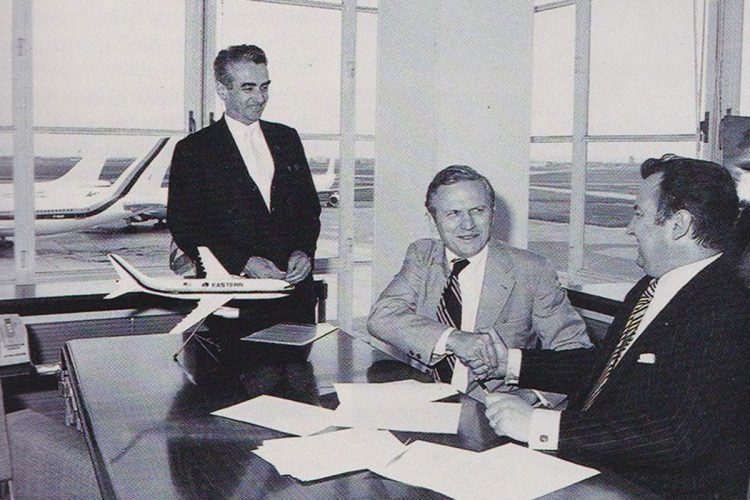

Borman had already enjoyed the A300 in 1973 when the plane was introduced to him, but the deal did not evolve until the consortium made a daring offer, lease four airplanes for six months before deciding on the purchase. The ex-astronaut ended up ordering 23 jets in 1978, making Eastern Airlines the first customer of Airbus in the US.

Cutting edge technology

One of the most admired aspects of Airbus is precisely the fact that it has invested in technological innovations that have become standard in the industry.

Prior to Airbus, commercial aviation did not consider composite materials, fly-by-wire, a cockpit with digital instruments or long-range aircraft with just two crew members, to name a few of the company’s most notable breakthroughs.

But it was the concept of the two-engine wide body as the most efficient solution for the commercial jets that Airbus paved its market success. Since 1977 the A300B4 has been awarded the first ETOPS (Extended Twin Engine Operations) certificate, the two turbofan aircraft have become increasingly reliable to fly long periods over the oceans, enabling new routes and making air tickets more affordable.

It is true that despite this, Airbus itself had its moments of disbelief in the future with two engines. By launching the A340 and A380, the European manufacturer tried to offer four-engine aircraft precisely at a time when they began their downturn in the market.

Fortunately for Airbus, the company kept its focus on twin engines like the A330 and the A350, an advanced jet designed to try to nullify some of the 787’s advantage, at a rare time when Boeing was bolder than its European rival in the last few decades.

Today it seems natural to see an A321LR cross the Atlantic on flights of more than 4,000 nm, but stating that this would be something normal 50 years ago would cause disbelief in the industry. This is the great legacy of Airbus.